The Jefferson Method: 5 Learning Secrets from America's Genius Founding Father

How a 250-Year-Old Study System Can Revolutionize Your Memory and Learning

Hey Kwik Brain,

What if the key to supercharging your brain wasn't hiding in the latest app or trendy technique, but sitting in the daily habits of one of history's most brilliant minds?

Thomas Jefferson wasn't just a founding father. He was a learning machine who spoke six languages, designed buildings, practiced law, conducted scientific experiments, played multiple instruments, and somehow found time to help birth a nation. His secret wasn't superhuman intelligence—it was a systematic approach to learning that modern neuroscience now proves works incredibly well.

Recent cognitive research examined Jefferson's specific learning techniques and found they align perfectly with what we know about optimal brain function. These 250-year-old methods can boost your memory, enhance comprehension, and accelerate learning in ways that'd make any modern student envious.

Here are the five core techniques that made Jefferson a genius, and how you can use them to unlock your own mental potential.

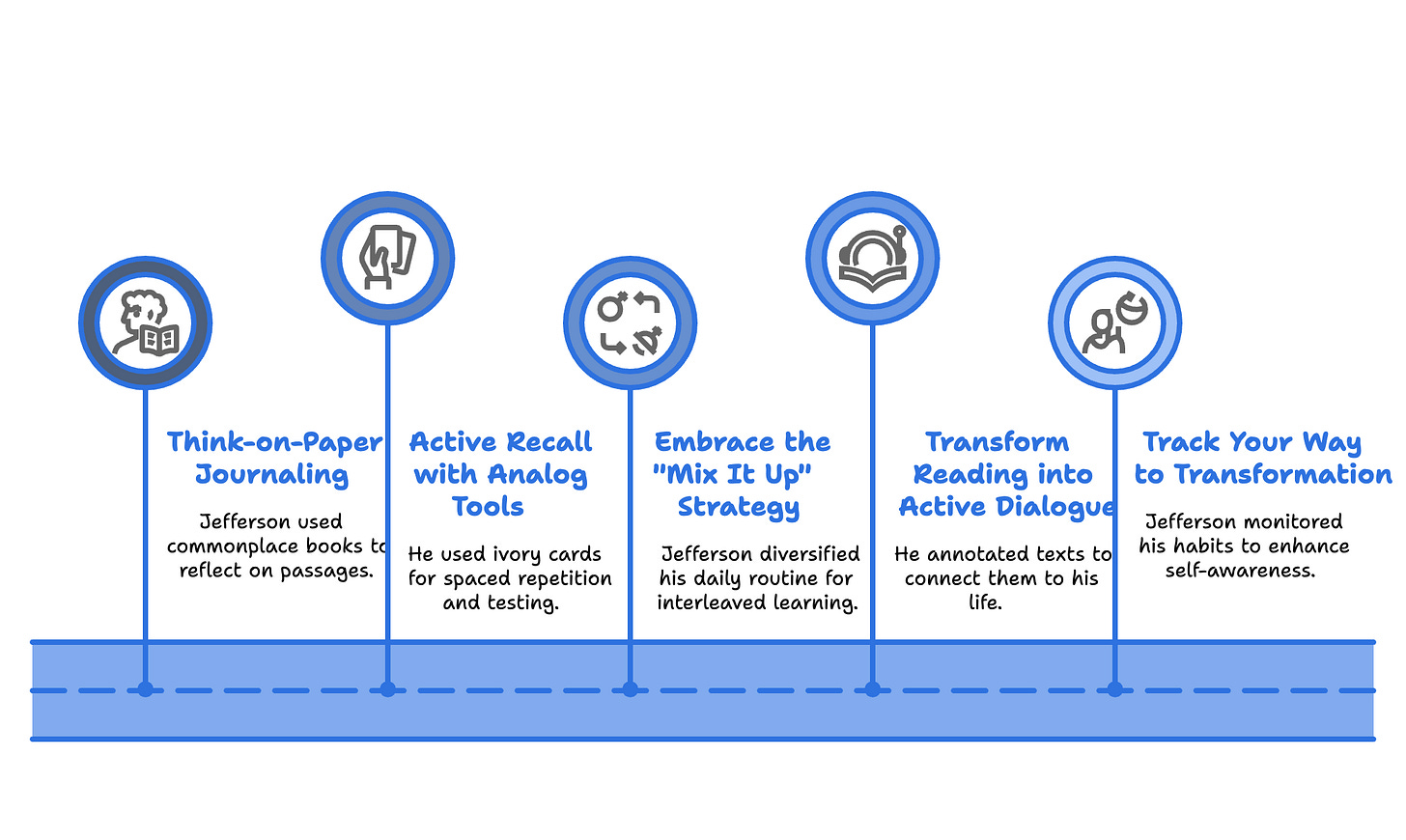

1. The Power of "Think-on-Paper" Journaling

Jefferson's famous commonplace books weren't just quote collections. They were thinking tools where he'd copy striking passages, then add his own commentary and reflections. Modern research reveals this practice taps into one of the most powerful learning mechanisms: the self-explanation effect.

The Science:

When you explain ideas in your own words, you create deeper neural pathways. A meta-analysis of 48 studies found that writing-to-learn practices significantly improve retention and understanding. Students who completed reflective journal writings throughout a course scored higher on tests compared to those who simply read the material.

The magic happens through elaborative writing. When you connect new information to existing knowledge and express why concepts matter to you, this process literally rewires your brain for better recall

.

Your Action Plan:

Keep a learning journal where you summarize key concepts in your own words. After reading something important, write a brief reflection on how it connects to your life or goals. Don't just copy quotes—add your thoughts on why they're meaningful. Review and expand on your entries regularly to reinforce the neural pathways.

Write to remember. When you explain ideas in your own words, you double your understanding.

2. Master the Art of Active Recall with Analog Tools

Jefferson carried ivory note cards, jotting down important thoughts during the day, then reviewing and transcribing them into permanent journals each evening. This wasn't just organization—it was brain optimization through spaced repetition and testing effects.

The Science:

A comprehensive 2021 meta-analysis of 222 classroom studies involving nearly 50,000 students showed that practice testing produces medium improvement in academic achievement compared to restudying. Students who practiced recall-based testing remembered about 67% of facts one week later, versus only 45% retention in groups who just re-read material.

The physical act of writing by hand engages deeper cognitive processing than typing. Students who write notes longhand have better conceptual understanding and memory of content. Jefferson's constraint of using small ivory cards forced him to distill information to its essence—a practice that enhanced his memory when he later reviewed the notes.

Your Action Plan:

Create handwritten flashcards for key concepts you need to remember. Test yourself regularly—try to recall the answer before flipping the card. Use a daily review system: morning for new cards, evening for review. Space out your reviews over days and weeks, not just the same session.

Quiz to recall. When you pull answers from your brain, you push them into long-term memory.

3. Embrace the "Mix It Up" Learning Strategy

Jefferson was famous for his diverse daily routine: Latin in the morning, law at midday, science in the afternoon, literature at night. This wasn't scattered thinking—it was interleaved learning, one of the most powerful techniques for building flexible intelligence.

The Science:

A 2019 meta-analysis of 59 studies found that interleaving—switching between different topics in one study session—produces moderate but consistent learning benefits. In one striking physics experiment, students who alternated between different problem types solved 50% more new problems correctly on surprise tests compared to those who studied one topic at a time.

Interleaving works by preventing mindless repetition and forcing your brain to constantly retrieve different strategies. It's like cross-training for your mind—you become more adaptable and better at choosing the right approach for each situation.

Your Action Plan:

Instead of studying one subject for hours, break your time into 45-90 minute blocks of different topics. Rotate between subjects that complement each other but require different thinking styles. Mix problem types within subjects—don't do 20 algebra problems in a row. Accept that this feels harder initially—the challenge is building stronger neural connections.

Mix, don't mass. Rotating your mental workouts strengthens your brain's adaptability and memory retention.

4. Transform Reading into Active Dialogue

Jefferson didn't just read Shakespeare—he annotated it extensively, relating characters and themes to his own life and values. He'd reread classics multiple times, each with fresh annotations and perspectives. This self-referential, active reading creates some of the strongest memories possible.

The Science:

Research on the self-reference effect shows that when you relate information to yourself, you recall it significantly better than through normal reading. Students taught to extensively annotate texts scored higher on comprehension tests with an effect size of 0.46—a meaningful improvement that compounds over time.

Multiple readings with reflection reveal new layers of meaning. While simple re-reading has diminishing returns, reflective re-reading where each pass involves new analysis can bolster long-term retention and insight. Reading literary fiction can even improve your Theory of Mind—the ability to infer others' thoughts and emotions.

Your Action Plan:

Read with a pen in hand—don't just consume, converse with the text. Ask yourself: "How does this apply to my life or goals?" Write marginal notes with your reactions, questions, and connections. Summarize key sections in your own words. Revisit important texts with fresh questions and perspectives.

Don't just read—engage. When you connect a text to yourself and question it, you remember it.

5. Track Your Way to Transformation

Jefferson meticulously tracked everything: weather patterns, garden cycles, reading lists, daily activities. This wasn't obsessive record-keeping—it was metacognitive training that enhanced his self-awareness and learning efficiency.

The Science:

A 2022 meta-analysis on student self-monitoring found moderate positive effects (average effect size ~0.47) on both strategy use and academic performance. Students who regularly monitored and recorded their behaviors performed better academically than those who didn't.

Habit tracking builds metacognitive awareness—thinking about your thinking. When learners self-monitor their comprehension and performance, they become more invested and active participants in their learning. The accuracy of this self-awareness correlates highly with memory performance.

Your Action Plan:

Track one or two key learning habits: study time, pages read, concepts mastered. Log what works and what doesn't—look for patterns in your performance. Review your logs weekly to identify optimal study conditions. Use the data to adjust your approach, not to judge yourself. Start small—tracking everything leads to overwhelm and abandonment.

What gets measured gets improved. Tracking your habits shines light on your learning, and light helps things grow.

The Jefferson Method in Action

These five techniques work together beautifully. Jefferson's commonplace books combined journaling and reading annotation. His ivory cards used active recall while his diverse daily schedule employed interleaving. His meticulous logs tracked it all, creating a feedback loop for continuous improvement.

You don't need to be a founding father to think like one. Start with just one technique that resonates with you. Perhaps begin a learning journal this week, or create flashcards for your next exam. The key is consistency—these aren't quick hacks but sustainable practices that compound over time.

Jefferson once said, "I cannot live without books." But more accurately, he couldn't live without learning. His methods turned reading into thinking, studying into discovery, and habits into transformation.

Your brain has the same potential. The question isn't whether these techniques work—the science proves they do. The question is: Which technique will you start with today?

Implementation Challenge

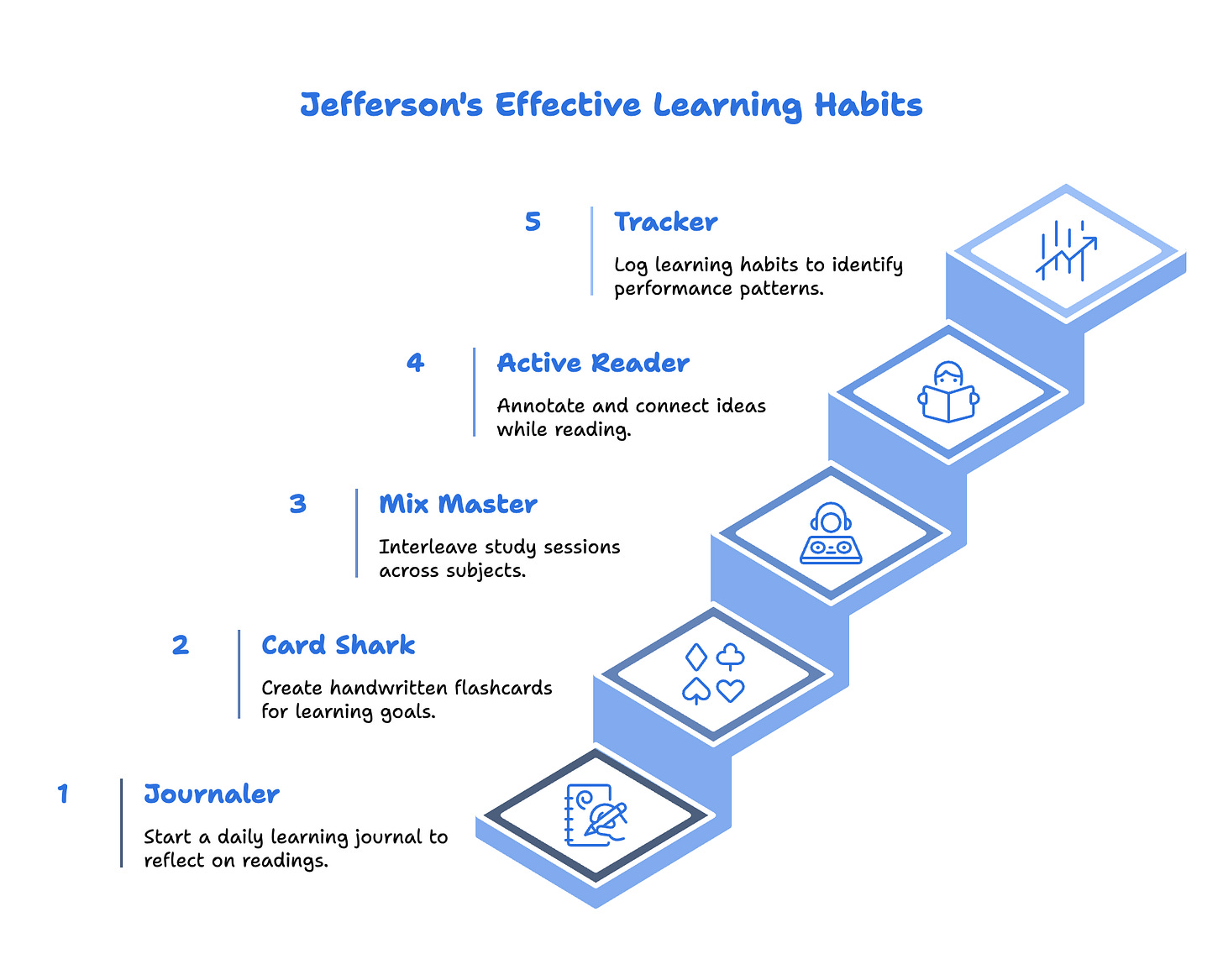

Choose ONE Jefferson technique to implement this week:

Journaler: Start a daily learning journal with reflections on what you read or study

Card Shark: Create handwritten flashcards for your current learning goals

Mix Master: Interleave your study sessions across different subjects

Active Reader: Read your next book with pen in hand, annotating and connecting

Tracker: Log one learning habit and look for patterns in your performance

The goal isn't perfection—it's progress. Jefferson built these habits over decades. You can start building yours today.

What small step will you take today to think like a founding father?

Check out one of my latest videos:

I have be piece mailing the newsletter to create a system like this. Now, I can pivot to this system. I thoroughly enjoyed and excited to get started today with this system. I have all of the tools...onward. 🤾🏾♂️

Question on this that I hope you can answer. I want to take action on this but have a question about journaling.

Action plan is to keep a learning journal where you summarize key concepts in your own words.

Currently, I am reading two books (Born to Walk by Mark Sisson) and Heavily Meditated (Dave Asprey). I also listen to podcasts (Dave Asprey / Ben Greenfield / Jim Kwik) which have information I pull from.

How do you organize the journal? Is it by day or topic? Meaning I just write down what I learned on that day. Example: if I read 30 minutes of one book, I journal on that. After that I could journal what I learned by listening to a podcast.

Or do you have multiple journals for each topic you are learning about? Then if I have quotes in each do I just have a quote journal?

Appreciate the insight!